Fuzzing is one of the rare automated vulnerability techniques that proved its efficiency for the past decades. This article aims to explain how to design and write a modern unix-compatible fuzzer, comparable to AFL++, libFuzzer or LibAFL, from scratch. It’s assumed the reader knows Rust and has a basic understanding of what a fuzzer is.

Today I’m releasing Astra, a Rust fuzzer made from scratch. This work wouldn’t have been possible without the excellent work of peers that published papers about novel approaches, developed, maintained and documented great open-source fuzzers. Open-source projects are often taken for granted, but in reality they exist because a small community is dedicating their time and efforts for everyone. Feel free to contribute in your way, resolve a good first issue on AFL++ or LibAFL, donate a coffee to the AFLplusplus organization, write documentation or simply use and share their work.

A special thanks to the community of Awesome Fuzzing discord, and particularly to @eqv @tokka @vanhauser-thc @domenukk @addisson for answering my innumerable (sometimes silly) questions.

Understanding fuzzer design: AFL.

Most modern fuzzers share common features: they execute a program under test, feed them mutated inputs and observe the result of their execution. The ideal beginning point to understand fuzzer design is to start by reading the afl technical whitepaper and the historical notes. In these documents, the author describes their desire to make a fuzzer that will be: fast, simple to use, reliable, and chainable.

Most of the features AFL offers are possible because of the coverage measurement, which allows to track branch (edge) coverage from the program under test, in this context this measurement is called a trace. The fuzzer maintains a global map of tuples seen in previous executions, which can be compared with an individual trace. When a mutated input produces an execution trace producing new tuples, it is preserved and routed for additional processing later on.

Along with new tuples, the fuzzer also considers coarse tuple hit counts, divided into several buckets: 1, 2, 3, 4-7, 8-15, 16-31, 32-127, 128+. Changes between the range of a single bucket are ignored while transitions from one bucket to another are flagged as interesting. The hit count behavior provides a way to distinguish between potentially interesting control flow changes, such as a block of code being executed twice when it was normally hit only once.

Typically this monitoring of edges and hit counts accesses a coverage map that records these values. In AFL this coverage map is named __afl_area_ptr

The fuzzer enforces aggressive timeouts, roughly 5x the initially-calibrated execution speed rounded to 20ms. This prevents dramatic fuzzer performance degradation by descending into tarpits that would not significantly improve the coverage while being 100x slower.

Mutated test cases that produced new state transitions within the program are added to the input queue and used as a starting point for future rounds of mutation. They supplement but do not automatically replace existing finds. The progressive state exploration approach outlined above means that some of the test cases synthesized later on in the game may have edge coverage that is a strict superset of the coverage provided by their ancestors.

To optimize the fuzzing effort, AFL periodically re-evaluates the queue using a fast algorithm that selects a smaller subset of test cases that still cover every tuple seen so far, and whose characteristics make them particularly favorable to the tool. This algorithm basically assigns a score for every entry based on multiple criterias such as: execution time, filesize. The non-favorite testcases are not disregarded completely, the odds of executing them is reduced to 1% if there is non-fuzzed favorite testcase left. Otherwise their execution chance grows to 5% if there is no new-favorite, and 25% for a non-favorite that has never been through a fuzzing round. This method is called by the author: culling the corpus.

The testcase file size has a huge impact on the fuzzer performances, not only because it makes the program under test slower but it also reduces the chance to mutate an interesting part of the testcase rather than redundant data blocks. Aside from low-quality testcases, some mutations can iteratively increase the size of the testcases. The built-in trimmer attempts to sequentially remove blocks of data with variable length and stepover; any deletion that doesn’t affect the checksum of the trace map is committed to disk.

Along with the built-in trimmer, a standalone afl-tmin tool exists, it is using a more exhaustive and iterative algorithm and attempts to perform alphabet normalization on the trimmed files. Text normalization is the process of transforming text into a single canonical form that it might not have had before, think of: madame curie -> radium came.

The tool will select the operating mode:

- If the testcase produces a crash it will keep any tweak that still produces the crash.

- If not, then it will run the instrumented program under test and keep only the tweaks that produce exactly the same execution path.

The fuzzing strategies, ergo which mutations are interesting or not, are detailed in the blogpost: binary fuzzing strategies: what works, what doesn’t. The feedback (code-coverage) provided by the instrumentation makes it easy to understand the value of various fuzzing strategies. AFL starts by a series of deterministic mutation strategies:

Walking bit flips: the first and most rudimentary strategy, it involves performing sequential, ordered bit flips. The stepover is always one bit, the number of bits flipped in a row varies from one to four. Across a large and diverse corpus of input files, the observed yields are:

- Flipping a single bit: ~70 new paths per one million generated inputs,

- Flipping two bits in a row: ~20 additional paths per million generated inputs,

- Flipping four bits in a row: ~10 additional paths per million inputs.

Walking byte flips: a natural extension of the walking bit flip approach, this method relies on

8-,16-, or32-bitwide bitflips with a constant stepover of one byte.- This strategy discovers around ~30 additional paths per million inputs, on top of what could have been triggered with shorter bit flips.

Simple arithmetics: to trigger more complex conditions in a deterministic fashion, the third stage attempts to subtly increment or decrement existing integer values in the input file, this is done with a stepover of one byte.

Known integers: the last deterministic approach employed by afl relies on a hardcoded set of integers chosen for their demonstrably elevated likelihood of triggering edge conditions in typical code (e.g.,

-1,256,1024,MAX_INT-1,MAX_INT). The fuzzer uses a stepover of one byte to sequentially overwrite existing data in the input file with one of the approximately two dozen “interesting” values, using both endians (the writes are8,16, and32-bitwide).Stacked tweaks: with deterministic strategies exhausted for a particular input file, the fuzzer continues with a never-ending loop of randomized operations that consist of a stacked sequence of:

- Single-bit flips: Attempts to set “interesting” bytes, words, or dwords (both endians)

- Addition or subtraction of small integers to bytes: words, or dwords (both endians)

- Completely random single-byte sets

- Block deletion

- Block duplication via overwrite or insertion

- Block memset

From the feedback obtained by the instrumentation it’s easy to identify syntax tokens, the detailed approach is detailed in the blogpost: afl-fuzz: making up grammar with a dictionary in hand. In essence mutation strategies are efficient for binary format but perform poorly when it comes to highly structured input such as text, messages or language. The algorithm can identify a syntax token by piggybacking on top of the deterministic, sequential bit flips that are already being performed across the entire file.

It works by identifying runs of bytes that satisfy a simple property: that flipping them triggers an execution path that is distinct from the product of flipping stuff in the neighboring regions, yet consistent across the entire sequence of bytes.

The fuzzer is attempting to de-dup crashes and consider a crash unique if any of two

conditions are met:

- The crash trace includes a tuple not seen in any of the previous crashes.

- The crash trace is missing a tuple that was always present in earlier faults.

AFL tries to address exploitability by providing a crash exploration mode where a known-faulting test case is fuzzed in a manner very similar to the normal operation of the

fuzzer, but with a constraint that causes any non-crashing mutations to be

thrown away. Mutations that stop the crash from happening are thrown away, so are the ones that do not alter the execution path in any appreciable way. The occasional mutation that makes the crash happen in a subtly different way will be kept and used to seed subsequent fuzzing rounds later on. This mode very quickly produces a small corpus of related but somewhat different crashes that can be effortlessly compared to pretty accurately estimate the degree of control you have over the faulting address.

To improve performance AFL uses a “fork server” where the fuzzed process goes through execve(), linking, and libc initialization only once, and is then cloned from a stopped process image by leveraging copy-on-write. The implementation is described in more detail in the article: fuzzing binaries without execve. It boils down to injecting a small piece of code into the fuzzed binary - a feat that can be achieved via LD_PRELOAD, via PTRACE_POKETEXT, via compile-time instrumentation, or simply by rewriting the ELF binary ahead of the time. The purpose of the injected shim is to let execve() happen, get past the linker (ideally with LD_BIND_NOW=1, so that all the hard work is done beforehand), and then stop early on in the actual program, before it gets to processing any inputs generated by the fuzzer or doing anything else of interest. In fact, in the simplest variant, we can simply stop at main().

The parallelization mechanism is periodically examining the queues produced by other local or remote instances, and selectively pulling the testcases that when tried out locally produced behaviors not yet seen by the fuzzer.

The binary only instrumentation mode relies on QEMU in user-emulation mode, QEMU uses basic blocks as translation units; the instrumentation is implemented on top of this and uses a model roughly analogous to the compile-time hooks. The start-up of binary translators such as QEMU, DynamoRIO, and PIN is fairly slow. To counter this, the QEMU mode leverages a fork server similar to that used for compiler-instrumented code, effectively spawning copies of an already-initialized process paused at _start.

The afl-analyse tool is a format analyzer simple extension of the minimization algorithm

discussed earlier on, instead of attempting to remove no-op blocks, the tool performs a series of walking byte flips and then annotates runs of bytes in the input file.

After reading the AFL technical specification, it appears that AFL is an out-of-process (meaning it spawns a child process) coverage-guided fuzzer. The big picture of AFL architecture can summarize as follow:

- The target under evaluation is compiled with a custom compiler that inserts instrumentation, then spawned as a child-process.

- The testcases are mutated with deterministics then later random strategies.

- The coverage (edge) is collected every fuzzing round, along with a block hit count.

- Interesting testcases are kept in queue and prioritized for future fuzzing rounds.

- Dictionaries are deduced from bytes that satisfy a simple property.

- Crashes are classified as unique based on their tuples.

- Exploitation exploration mode uses mutation to produce interesting similar testcases.

- Parallelization is achieved through shared QUEUE with new testcases tuples.

- Binary-only fuzzing relies on custom QEMU userland instrumentation.

Of course, dozens of other fuzzers exist and each have their own specificity, however, AFL laid out the way for modern fuzzers and we can find similar features in a lot of recent projects. A great way to learn more is to read the code of other state-of-the-art fuzzer such as AFL++, LibAFL, cargo-fuzz, etc.

Designing a fuzzer architecture: Astra.

The main goal of Astra is to provide a simple to use and reliable fuzzer. For these reasons, and because it is objectively the best language in the world, this fuzzer will be written in Rust. It should be able to run on any UNIX distribution that supports Rust, provide a clear interface to the user and produce interesting results. The design is greatly inspired from AFL but for different reasons some choices differ from the old AFL version.

From the analysis of AFL architecture we can retain a few core concepts: corpus minimization, instrumentation - code-coverage, determinism, parallelization, mutation engine and fuzzing strategies, target observation and reporting. This constitutes a solid foundational design for the fuzzer, Astra is to be composed of multiple modules, each one designed to achieve a specific task.

- CLI: Command-line interface allowing the user to set some parameters to the fuzzer.

- Collector: Collects corpus and transforms it into a memory-efficient collection.

- Instrumentation engine: Transform the program under test into an observable target that returns coverage per execution.

- Monitor: Monitor the state of the program under test after each run.

- Observer: Observe the coverage achieved by each input fed to the program under test.

- Mutator: Mutate inputs to achieve better coverage.

- Reporter: Report the statistics gathered by the observer and the monitor.

- Runner: Run the program under test and feed them a mutated input.

To understand a bit better how to design Astra, it is important to describe the workflow the fuzzer should follow to effectively stress a program under test. The first step is to instrument our program under test in order to observe code-coverage feedback during its fuzz execution, this is achieved by AFL with a custom compiler that injects custom assembly in the program under test, Astra will skip this step and let the user directly instrument their target with sancov.

The second step is to gather the corpus, the initial valid files we provide the fuzzer with, and transform them into mutable format, so that our third step, the mutation engine, can perform mutation on the testcases. The mutation engine will, based on deterministics or random approach, fuzz interesting (or not) testcases, the runner will then take a testcase candidate and run it against the target. After that the observer and the monitor will work in parallel to return precious information to the fuzzer: whether or not this testcases produced a crash OR interesting results.

The graphical interface, in our case the TUI, will display these results to the user. This loops until the user decides to end the fuzzing campaign and voila! In summary, we can view the fuzzing process like this:

Target instrumentation

|

|

v

Corpus collection and Transformation

|

|

|

v

+-----------------------------------------------+

| Fuzzing LOOP |

| |

| Mutation engine | |

| ^ +---------> Runner |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | v |

| | |

| +---------------------Observer |

| | |

| | |

| | |

| Reporter <----------+ |

| |

| |

+-----------------------------------------------+

Astra needs to be compatible with Linux and Mac. The fuzzer logic is to be compiled into a static library, linked to the target program, that will feed inputs, monitor execution and perform reporting.

To test the fuzzer during the development phase, I created several test programs:

- A simple nothing program that allow to test the performance bottlenecks of the fuzzer

- A reader that reads a file from inputs and performs a few actions if some characters are detected.

- A parser that reads and parses data from a file input.

Instrumentation Engine

Astra needs to collect code-coverage on Linux, Windows and MacOS, thankfully clang offers code-coverage instrumentation and is available on all of these platforms. The setup is somehow trivial, we simply need clang and some LLVM tools that you can install by following their getting started guide. It offers multiple coverage instrumentation methods, like source-code coverage or a gcov compatible instrumentation. The interesting one is edge-coverage because it offers a very granular coverage metric, this feature is provided by SanCov.

SanCov inserts calls to user-defined functions on function, basic-block or edge levels. An edge represents basically a control transfer between a basic block A and a basic block B, themself being simply a straight-line code sequence with no branches in except to the entry and no branches out except at the exit. In other words, edges allows us to track the branches of our executed program under test, and returns which path has been traveled or not per execution.

The documentation specifies that with the flag -fsanitize-coverage=trace-pc-guard the compiler will insert __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc_guard(&guard_variable)for each edge, and each edge will have its own guard_variable (uint32_t). A guard can be seen as a unique ID for an object. A few other flags are available too but for the moment the most important information is that the functions __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc_* should be defined by the user.

To understand how to implement the __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc_guard function, let’s have a look at the SanCov example. We can implement our own version and try it against the simple_reader.c example, first we need to create a simple_pc_guard.c file, then we need to compile our reader and link it against our trace-pc-guard binary. New coverage is obtained and their guard value displayed when a new edge is discovered. A simple rust binding simple_coverage_example.rs is possible too.

The target binary has to be linked to the runtime library, since the goal is to have an easy-to-use fuzzer, it is better not to ask the user to link their target manually. For this reason this task has to be automated by astra_linker, its job will be to link the target binary to the runtime library that contains Astra custom __sanitizer_cov_trace_guard implementation.

One hacky way to achieve this is to take the user target program as a PathBuf from the CLI, transform it into a string and use it as an argument to spawn a process with Command::new. After that we can add a simple Command spawn and give it the correct instructions. Cargo will compile the custom sancov implementation into a static library and link it to the user provided target.

The way AFL tracked code coverage was rather trivial but efficient, it starts by assigning a random ID to the edge, then performing an exclusive or on last_basicblock and current_basicblock to obtain a pseudo-random edge id, that is incremented by one. Basically the idea is that it allows to track edge coverage with minimum collision with a good performance.

cur_location = <COMPILE_TIME_RANDOM>;

shared_mem[cur_location ^ prev_location]++;

prev_location = cur_location >> 1;

The custom sancov implementation that allows to track edge-coverage is statistically linked to the user target binary, how does it write to the edge-map the fuzzer uses to collect coverage? Here comes in place the concepts of shared_memory and mmap. Wikipedia defines shared memory as: “a memory that may be simultaneously accessed by multiple programs with an intent to provide communication among them or avoid redundant copies.” and the AFL’s documentation states that: “The shared_mem[] array is a 64 kB SHM region passed to the instrumented binary by the caller. Every byte set in the output map can be thought of as a hit for a particular (branch_src, branch_dst) tuple in the instrumented code.”.

Astra is an out-of-process fuzzer, thus it needs a way to communicate with the child processes. To communicate between processes we can use different means called IPC mechanisms, plethora of methods exist: pipes, sockets, shared file, shared memory. Having performance in mind, Astra will use shared memory, this is the fastest a process could share information to another one. To understand this mechanism I crafted a very simple example of a reader and a writer using shm_open and mmap to read and write directly to memory. You can run the example by using the command: make run.

If you want to learn more about the POSIX shared memory standard, it is well documented here: https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man7/shm_overview.7.html.

The flow of creating a shared memory space can be described this way: we first use shm_open to create a shared memory region, then we use ftruncate to size it accordingly to our data, after that we use mmap to map the region to our internal representation, here it is struct MyData *data, from now on any operation performed on data struct will be written onto the shared memory data, once finished we munmap the map to detach from it, then shm_unlink to remove the shared memory region.

Working with libc in Rust can be challenging, thankfully some crates provides good Rust bindings allowing us to leverage shm from rust such as the rustix crate, which provides efficient memory-safe and I/O-safe wrappers to POSIX-like, Unix-like, Linux, and Winsock syscall-like APIs, with configurable backends. A rust example of a shared memory read and write using rustix can be found in the rust_shm folder.

The function linux shm_open offers the possibility to create or to attach to an existing file, we can pass a flag that specifies if we want to create the file if it doesn’t exist or if we simply want to read or write from it, from there it’s rather trivial, we can create a file in the parent process with a specific name, then open it in the child process at startup. The rust crate rust-ctor offers an initialization capabilities to function using the macro #[ctor] which means the function will be run at process startup. Note that we could also use __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc_guard_init to call the initialization of the shared memory.

We define a static mut pointer that will hold the returned ptr from mmap(), and assign it mmap() returned value. It’s important to define a size for our map, we will use the maximum size a 64-bits integer can hold in rust 262_144 by declaring a const MAP_SIZE: usize = 262_144. This value is to be used to truncate the shared memory file by ftruncate which takes a u64 as input. The edge map will follow the same design old AFL did, except a little specificity here is that we need to create a slice from raw parts using the shared memory pointer and the size of the map, which forms a mutable slice from a pointer and a length.

AFL design specifies tracking the edge hitcount, in other words “how many times the same edge has been seen” and then it classifies them in different buckets. The bucketization groups the following hitcount: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 16, 32, 128+. Any transition from one bucket to another will be flagged as interesting.

To determine if an input is interesting, the edge map obtained by a process is compared to a global map, this global map lives in the parent process and grows every time a new hitcount or new edge is discovered.

You can play with this early version of Astra by running the command: $ git checkout 1b38cb98f7901e7857f673c739b6cc1f4ec4251then run the project against a binary instrumented with trace-pc-guard.

Corpus Collector

The corpus is the collection of initial testcase the user provides to the fuzzer; it is to be transformed into a format that allows the testcase to be mutated. Since the fuzzer goal is to be run in parallel mode, the corpus will be shared by different mechanisms, for that reason we use an atomic reference vector of vector of bytes to represent it Arc<Vec<Vec<u8>>>. The input_dir entry is added to the CLI and the corpus is collected in the main process. You can check this version at: eec07ed9b59ec7c89cfaa542c69dd9b631f6836a

Observer

The observer part is responsible to determine if an input is interesting or not, as we saw earlier we can simply classify input as interesting by answering the questions: have we discovered a new edge ? Has the edge hitcount bucket increased ? A structure CoverageFlags holds two boolean values that are used as flags for this mechanism, the corresponding code is in astra_observer/src/coverage.rs. You can check an initial version at: eec07ed9b59ec7c89cfaa542c69dd9b631f6836a

Worker

The worker is the heart of the fuzzer, based on the number of CPU cores the user provides, the fuzzer will spawn the corresponding number of thread workers, each one mission is to feed a testcase from the corpus or the queue to the target, observe and report the result.

Parallelism can be described as a method to execute multiple tasks at the same time on different cores, these tasks could be completely isolated or synced between cores. In old AFL, the fuzzer shared a corpus copy to each thread to avoid locking the shared global_map to other threads, then performed an update of the shared global_map only every now and then when new testcase are found. The writers have the priority to write into the shared global_map to avoid starvation, meaning other threads keep reading it and the writer can never write an input. The workers are run in a thread pool design, feeding inputs from the queue or the corpus. If you want to read more about this you can read the excellent book: Rust Atomics and Locks.

Thankfully Rust offers more modern, fast and reliable mechanisms to do that. In Astra we will use the crate crossbeam and its channel to create a priority list of inputs that yielded interesting results in a previous run, a normal list of inputs collected from the corpus, a global map owned only by the main thread. Channels are used to pass data without having to share them amongst threads, which not only scales well but also prevents a lot of overhead from locks. You can check an initial version of astra_worker/lib.rs and astra_worker/worker.rs at this checkout: ea65117f70123e325af9d1ac075e341de24f32cd

Mutation Engine

Feeding inputs to a target is great but it’s important that the fuzzer mutates them in order to discover new edges. There are plenty of different kinds of mutations, on bits level, bytes level, or even segments. Some of them are inserting, replacing, swapping, deleting from the mutated input. More advanced mechanics exist such as splicing or even text normalization. Other mutators operate on highly structured input such as grammar mutator, which allows to produce syntactically correct inputs.

A good first start is to implement simple havoc mutation that will operate on one or multiple bytes, using AFL and LibAFL as inspiration. You can check the mutation engine at astra_mutator/havoc_mutations at this checkout: 233a5e3038da98c0127d544a1dc71463a8d344cf. By running the fuzzer with a simple input containing the letter b it is now able to find all the branches of the small test program.

Monitor

This component collects termination signals of the program under test, we can simply observe the child process exit code, if the signal is not 0 this means some problem occurred. The fuzzer then saves the file with a unique hash based on the file content in the output/crashes/ folder. You can check the monitoring at astra_monitor/lib.rs at this checkout: b33c868b8b7814b398171f332cd25dc866d3f08f.

Statistics

Astra isn’t super original, a good starting will be to cover these essentials metrics:

- Runtime

- Last time since a new path has been found

- Total path or hitcount found

- Total crashes

- Total execution

- Execution speed

You can checkout the commit 8fb92493de6af1c55970bc4d7504a43916a83691 and look at the code at astra_tui/lib.rs and astra_worker/lib.rs / astra_worker/worker.rs if you are curious to see this initial implementation.

Installer

In a real-world scenario the user will desire to use the fuzzer against existing software that probably uses compiling systems such as Makefile, Just, Ninja, and so on. For this purpose it’s very convenient to have the static library libastra_sancov.a on the user’s system.

The first step is to actually distribute Astra and its components properly to the host system, there are plenty of interesting but rather complex projects to do that in Rust such as dist (formerly cargo-dist), cargo-bundle and so on. For simplicity, we’ll use a good ol’ bash script that, when executed, will compile the project, save the static library libastra_sancov.so in the right folder and install the astra package on the system. You can check this script at this commit: 8ab0255d3b9f96dcfa9325ad9220253a207f6d24 in this file: utils/install.sh.

It is now possible to instrument any target with the following command: CC=clang CFLAGS=” -fsanitize-coverage=trace-pc-guard -fsanitize=address” LD=clang LDFLAGS=”-lastra_sancov -fsanitize=address.

Making a cc and cxx wrapper

AFL and others offer a compiler wrapper so that users don’t have to pass flags themself, this is exactly what astra do too. It ships with two compilers astra_cc and astra_cxx that can be used with building scripts such as Makefile and others. You can check these wrappers at this commit: dc52a1c01d326074e27cf81df195d724ff42238a in these files: astra_cc/src/lib.rs and astra_cxx/src/lib.rs. Note: We do not need a linker in the fuzzer anymore since linking now happens at compile time.

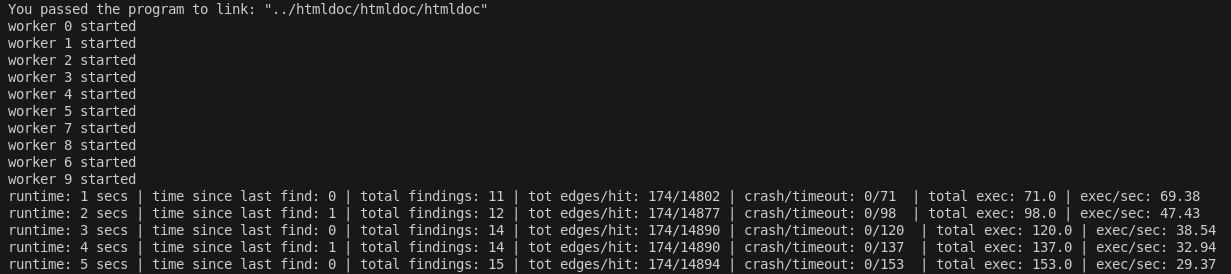

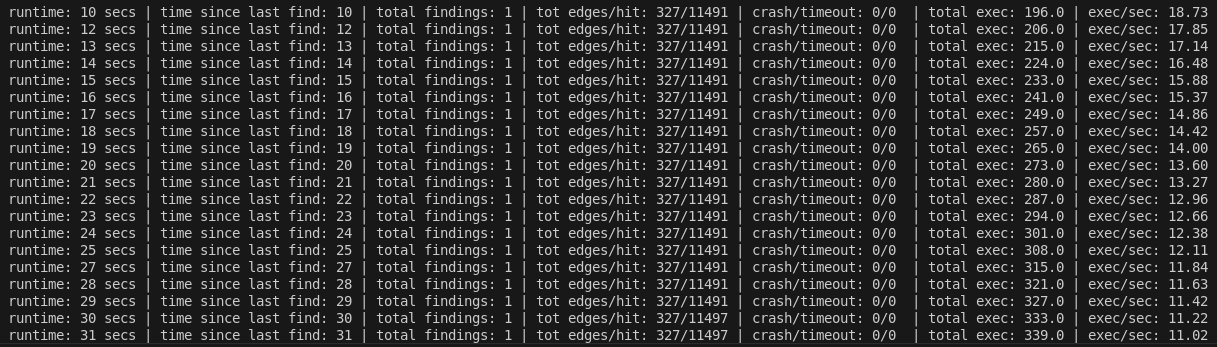

To test these wrappers I used astra_cc against the tool htmldoc with: CC=astra_cc CXX=astra_cc LD=astra_cc ./configure && make -j(nproc) and run Astra against an instrumented version of htmldoc.

We are now fuzzing an instrument binary with our own custom coverage!

Accepting trailing arguments and improving the CLI

AFL doesn’t specify arguments itself, it receives it from the user and injects the filename at the position the user specified @@. For this reason we are going to implement a way to catch trailing arguments, read arguments after --, and inject the filename accordingly. It’s also a good time to improve the CLI more generally.

Clap offers a good way to catch trailing arguments, basically anything that is after -- will be stored in a Vec<String>, we can then simply iterate over the vector, catch the @@ symbol and inject the filename at the right place. A simple version can be found in the file astra/src/main.rs and astra_cli/src/lib.rs at this checkout: dc52a1c01d326074e27cf81df195d724ff42238a.

Catching timeouts

Some bug classes do not result in an immediate crash but in a hang of the target program, for example a function could expect an argument to never be greater than a certain size, but not enforce any verification, which could result in infinite loop. It’s important to catch these errors too without flooding the user with false positives, for that reason the default value of a timeout is quite high and it’s up to the user to adjust it accordingly.

Writing a timeout catcher can be complex because we have to deal with signal handling and of specific cases, thankfully there is the crate wait_timeout that already provides a handy wait_timeout() function. Of course we need some small adaptations in the worker to return the results, crash or hangs, to the main thread. If we set the CLI default with a timeout of 10ms we can see it catches errors properly:

You can find an example at astra_worker/src/worker.rs at this checkout: 9c05b4f5ef2e3adfba21d094ee347f92a7a5645f Note: the timeout is defaulted to 10ms in the CLI in this example! Voila! Astra is now essentially a rudimentary but complete fuzzer! Hourra!

Conclusion

Astra shows that building a modern fuzzer isn’t magic: it’s a set of simple mechanisms engineered carefully. By combining fast coverage feedback, a shared map, a basic corpus loop, and aggressive mutations, we already get something surprisingly effective and scalable. This project is intentionally educational, so there’s still a lot to improve: scheduling, minimization, and deeper heuristics, but the foundation is solid.

If you want to truly understand fuzzing, writing one is the fastest path.